Scientists from IBM Research and Mars, Incorporated have established the Consortium for Sequencing the Food Supply Chain, a collaborative food safety platform that will leverage advances in genomics to further one’s understanding of what makes food safe a collaborative food safety platform that will leverage advances in genomics to further understanding of what makes food safe.

Dave Crean, Vice President of Corporate Research & Development for Mars, Incorporated, tells Food News International more.

FNI: How did this collaboration come about?

Crean: Arguably, ensuring food is safe is one of the biggest, most fundamental public health challenges of our time.

Current approaches to food safety are working, but not consistently and not everywhere, and the impact can be devastating.

The World Health Organization recently announced that in 2015 World Health Day will be focused on food safety, and with good reason.

Data on food safety related illnesses is notoriously patchy but in 2011 the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimated that in the US alone foodborne diseases affected one in six people and resulted in some 3,000 totally avoidable, tragic deaths and a cost of some US$80 billion to the economy.

Globally, the estimates are much less reliable and likely to be significantly underestimated.

Current thinking places the human toll of unsafe food and water at about two million deaths annually – unacceptable and avoidable.

The food supply chain is made up of millions of microbes.

Our hope is to understand all of the relationships among all the life forms in a factory environment and learn the conditions that enable pathogens to thrive.

Is salmonella present simply because it found its way there on some dust or because it has some resistance factors that are being given to it by another organism that we do not currently test for?

At this point, we just don’t know.

There might be subtle relationships between populations and the microbial ecosystem that we can begin to understand through genomics.

Of course, it’s a big data challenge as well.

This is where the guys in IBM really come into their own.

There’s a lot of computing power and analysis required.

Our hope is to get a very different story about organisms, why they’re present, how they’re controlled, why they thrive, why they don’t thrive—and to answer some of the questions that we’re not able to answer today.

Together with IBM and the Consortium for Sequencing the Food Supply Chain our aim is to explore and apply the techniques of genomics to better understand the safety of food supply.

FNI: What are the immediate goals for this consortium?

Crean: What’s clear is that we – industry – need to think and act differently about how we address food safety.

A key challenge for food safety experts today is that typically when they test food they only have a chance of finding what they set out to look for.

If they are testing for Salmonella, they won’t find Listeria.

We don’t know the nature and influence of the full microbiome.

It sounds obvious but that’s a huge gap in our understanding of what’s really going on in our global food supply chain and in food handling facilities around the world.

Current procedures offer no opportunity to understand the full microbial ecology of an environment or the suite of potential food safety risks present.

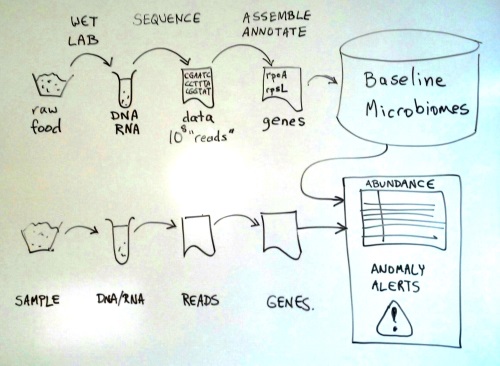

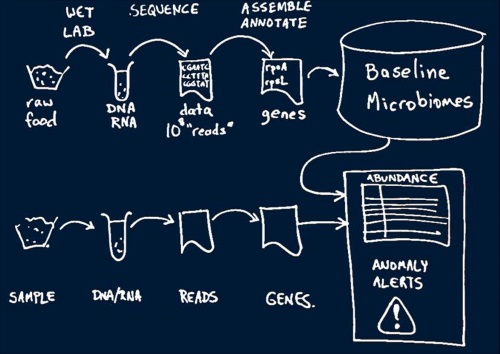

As a first step, the consortium will conduct the largest-ever metagenomics study to categorize and understand micro-organisms and the factors that influence their activity in selected raw materials and finished products.

This first step begins to answer the question “can we use the microbiome of raw materials and the factory as a predictor of food safety risk?”

Understanding the microbiome may enable us to discover new risk indicators and risk management strategies.

It will also provide us with an unprecedented ability to attribute sources of microbial issues through the supply chain and provide data to help drive post market surveillance.

FNI: How will these goals building stones for more projects in the future?

Crean: Genomics opens up a whole new area of understanding.

It looks at all of the genetic material present in a sample and through the application of clever mathematics and biochemistry reconstructs that genetic material into identifiable genomes.

Everything is identified and suddenly we have the ability to describe (and therefore understand) whole microbial eco systems.

What’s more we can track them with great precision.

That’s how we see it.

We’re thinking that maybe the factory has a microbiome just like your body has a microbiome.

If we can understand the relationships, we can potentially start to influence the microbiome by shifting the conditions in the factory, whether that’s how we clean or the raw materials that we use, the temperatures that exist, or how wet or dry it is.

For the first time we’ll be able to ‘fingerprint’ materials and production environments and, we hope, understand at a fundamental level what is driving key elements of food safety risk.

FNI: What does it take for a successful collaboration, especially with various stakeholders from the public and private sectors?

Crean: When there’s an illness outbreak, it affects everybody.

It affects all our businesses and shakes public confidence in governments and the supply chain generally, even if you haven’t been directly involved, it’s very difficult to recover that confidence.

So if we have information about food safety, anything that can be used to avoid issues or resolve existing issue more quickly we’re anxious to share it.

FNI: What has the food industry done right in ensuring food safety in factories?

Crean: There are great examples of food safety practice and hazard analysis.

Yet the food safety challenge doesn’t feel like it’s getting any easier.

That’s partly because there’s more transparency and better reporting, so the problems are more apparent.

But you can never have complete confidence about what’s going on 24 hours every day, seven days a week, 365 days a year.

That’s why we’ve been talking with IBM about a new approach.

We’re hoping to develop a system that’s more probabilistic.

FNI: What areas does the industry lack in terms of ensuring food safety in factories?

Crean: A lot of people think that all you need to do is take a sample and if there’s no salmonella, listeria or e.coli present, then that tells you it’s safe.

But if you take 300 samples from every single delivery, it would tell you that there’s a 95% probability that no more than 1% is contaminated.

But 1% is a lot!

And 300 is a lot in terms of processing samples.

So you can’t take enough samples.

And by the way, those statistics are misleading.

Pathogens tend to be in clumps, not randomly distributed.

So you literally are looking for a needle in a haystack.

You can’t do it by testing.

It’s not a reliable method.

Mars and the industry as a whole spend a lot of money on testing and we get very little information back.

Is the level of risk increasing?

Is it decreasing?

We find that very hard to see routinely from the testing that we’re doing.

FNI: How will the Consortium for Sequencing the Food Supply Chain help food manufacturers address these vulnerable areas?

Crean: The aim of the Consortium is to help us to better identify when and how food safety risks emerge, particularly within a factory setting.

This would enable food producers, retailers, distributors and public health officials to predict, localize, and identify spoiled or contaminated food ingredients anywhere in the supply chain and prevent them from being processed, distributed or eaten.

My hope is that we’ll be able to give factory managers and food manufacturers much more detail about what’s in their factories, but more importantly, provide new strategies for making sure that their environments are as safe as they can possibly be.

That may not be about simple interventions like cleaning, which is typically the case today.

For example, it might involve encouraging the growth of specific organisms that may be protective versus salmonella.

FNI: How will this platform benefit the larger food industry community beyond the US, such as Asia and Europe?

Crean: Our suppliers don’t just supply Mars, and so if we can help them get better about their practices, we’re helping everyone.

When I talk to senior management about the potential here, they’re delighted that we can potentially improve the performance of our business, but they’re also very excited about being able to make a contribution to food security globally.

For the first time we have the tools and the partnerships in place to really see the issue at the fundamental level.

The aim of the metagenomics study is to give food safety practitioners a much better understanding of microorganisms, particularly bacteria, fungi and viruses, and how they interact in different environments.

I think our ability to spot issues when they are small is going to be unparalleled.

Being able to quickly spot where these organisms are coming from, being able to trace them forensically using new genomic techniques, and being able to really zero in and fix the issue quickly is going to minimize risk to public health and to industry.

Maybe we are being overly ambitious.

It’s a very high risk project.

But, you know, if you don’t give it a go, if you don’t kick the ball, you’re never going to score a goal.