In view of the extreme toxicity of the botulinum neurotoxin, one of the primary targets of the food industry is to prevent the growth and neurotoxin formation by Clostridium (C) botulinum in food.

The bacteria C. botulinum forms the highly potent botulinum neurotoxin.

This is the most poisonous substance we know of – just 50ng is sufficient to kill a human, or the equivalent of a grain of rice could kill two million people.

The botulinum neurotoxin is responsible for botulism a severe, but rare, neurological condition.

Symptoms include slurred speech, blurred vision, muscle weakness and muscle paralysis, that spreads down the body.

If left untreated botulism may result in death due to respiratory failure.

Practising food safety habits

In the food industry, operators have been identifying stringent control measures and ensuring that these are always effectively applied.

One example is the “Botulinum cook” given to low acid canned foods.

This heat treatment of 121°C for three minutes was devised almost one hundred years ago, and when delivered effectively ensures the safe production of low acid canned foods.

Consumers should also ensure they handle food in the way designed by the manufacturer, such as storing foods at the correct temperature, and adhering to use-by-dates.

Consumers should also discard bulging/damaged cans and any preserved food that gives off a foul smell.

Germination of bacteria

Researchers at the Institute of Food Research (IFR) for example continue to study C. botulinum, so that the food industry can develop new science-based approaches to prevent foodborne botulism.

One target is to better understand the life cycle of the bacteria.

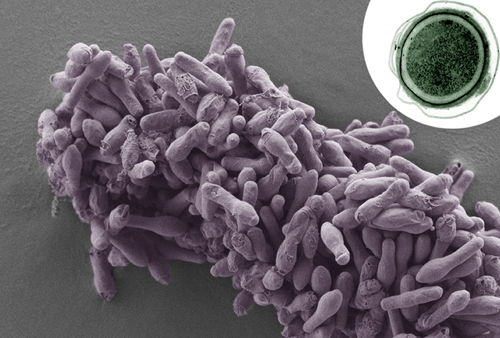

C. botulinum exist in the environment as spores, which are in many ways like the seeds of a plant.

They protect C. botulinum from adverse treatments, as they are very heat resistant.

In order for C. botulinum to be able to cause foodborne botulism, the spores need to germinate and form cells that multiply and form botulinum neurotoxin.

Until now little has been known about the spore germination process in C. botulinum.

The spores only germinate in a suitable environment, and in the presence of nutrients such as amino acids, which they sense through specialized receptors.

These receptors then trigger a chain of events that lead to the spore becoming a cell.

“Turning off” genes

Through analysis of the genome of a strain of C. botulinum that IFR researchers have previously sequenced, they have identified genes that seem to be involved in the spore germination process.

The researchers then systematically turned off these candidate genes to identify those that were crucial for germination.

Their research, recently published in the journal PLOS Pathogens, identified two sets of genes that C. botulinum needs, and which must act together for the spores to germinate in response to the correct stimulus.

This has allowed the researchers to develop a better understanding of exactly how the spores germinate, and as more is understood of the complex germination systems in C. botulinum.

This information may be used to develop knowledge-led approaches to interrupt this process, which would greatly help control C. botulinum and potentially other pathogenic clostridia, for the food industry.

Continuing research

IFR researchers continue to investigate spore germination and germination inhibitors with the ultimate aim of developing knowledge-led approaches for food safety.

Additionally, they are investigating the biology of neurotoxin formation, and the variability between strains of C. botulinum.

The researchers also work with the food industry and regulatory bodies to ensure the safe development of food produced according to new formulations.

Story by Professor Mike Peck and Dr Jason Brunt from the Food Safety Centre at IFR.