A study at the Institute of Food Research (IFR) has shown how common chemicals found in foods and oral hygiene products can alter the structure of the protective film that human saliva produces. Saliva has a number of functions, one of which is to coat our mouth and teeth in a thin film, less than a thousandth of the thickness of a human hair.

This protein-rich film is called the salivary pellicle. It is the primary interface between the external environment and the hard and soft tissues of the mouth, and so plays an important role in oral physiological and pathological processes.

For example, it provides a barrier to the dissolution of teeth from dietary acids, and also lubricates the mouth, facilitating the consumption and processing of food. The salivary pellicle is frequently exposed to various ingredients in food and oral hygiene products, such as sodium tripolyphosphate and sodium dodecyl sulphate.

The study found that both these ingredients change the physical structure of the pellicle, but in slightly different ways.

In some cases the remaining pellicle displayed a curious structural transformation from a soft but dense pellicle, to a more diffuse, rigid pellicle.

These structural changes may be important in determining how well the pellicle protects our mouth and teeth, but may also influence our perception of food.

For example, most people have experienced that dry, puckering type sensation when they eat certain types of fruits, for example pears, or drink red wine.

These are food sources rich in polyphenols that can disrupt the salivary pellicle resulting in a temporary loss of lubrication experienced as dryness in the mouth.

The importance of the pellicle becomes most apparent in people who suffer from dry mouth syndrome, or Xerostomia.

Without adequate saliva in the mouth to produce an effective salivary pellicle, these individuals can suffer from difficulty in swallowing, chewing, speaking, increased dental caries and mucous membrane damage.

Unfortunately, currently available artificial saliva only provides limited relief to these symptoms, principally because they do not adequately mimic the complex interfacial film forming properties of human saliva.

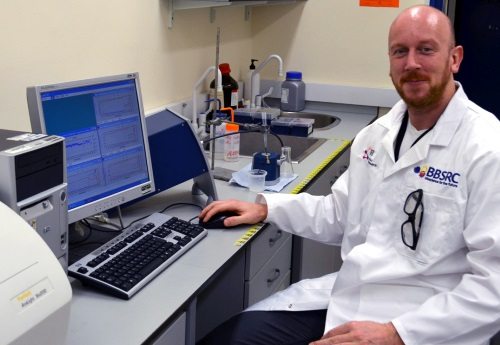

“This new knowledge not only augments our current understanding of the salivary pellicle, which is important for the development of more realistic salivary mimetics, but also demonstrates how certain ingredients are able to alter the structure of the salivary pellicle,” said Dr Anthony Ash, who carried out the research at IFR.

“These changes may not only influence the pellicle’s ability to perform a protective role in the mouth but may also impact our perception of foods.”

Dr Ash was funded by a Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council industrial Collaborative Awards in Science and Engineering partnership with GlaxoSmithKline.